A world with plenty of capital

Since the events of what is commonly described as ‘The GFC’, much attention has rightly focused on household and private debt as one of the drags on economic recovery. Commonly referred to as ‘de-leveraging’, households in most developed countries have embarked on a significant savings surge as they attempt to repair balance sheets from the credit expansion of the early 2000s.

But if there was too much household (private) debt, where did all of the deposits come from to fund the debt?

The answer still surprises many people. The deposits came from… nowhere. That is, when modern banks approve and extend new loans, they simultaneously create an equally sized deposit.

The idea that loans create deposits is still not widely recognised in modern economic theory, yet this great insight is beginning to gain traction globally. S&P recently endorsed this idea (see "Repeat after me, banks do not lend out reserves"), as did the Bank of England ("Money creation in the modern economy").

And while policy makers rightly grapple with the issues of private sector deleveraging, owners of capital have a different, but no less serious problem. The credit bubble created new capital and diluted existing capital. In short, there is now an abundance of capital seeking a relatively static universe of investment opportunities.

The Japanese experience

Nowhere is this issue more prevalent than Japan. The 1980s and early 1990s saw a massive credit bubble in both the household and business sectors. When the bubble burst, policy makers reacted by dropping interest rates to near zero – where they still are today.

The debt bubble creates a capital bubble, with nowhere for capital to earn a meaningful return given the zero interest rate environment.

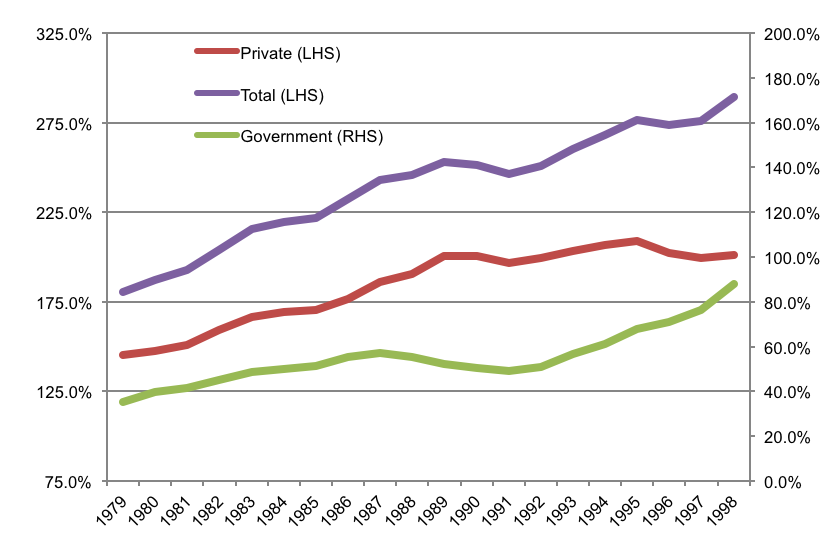

Japanese Public and Private debt as % of GDP

However, surely with all of that additional capital there is cash ready to invest, so that is good for share prices, right?

Cash on the side line

How often have we heard this term? It is generally used as a buy signal. There is record cash on the side line, so ‘get in now, because everyone else will buy soon too’. And with all those new deposits created from the credit boom, why did Japanese equities perform so poorly for the following 20 years?

It is a fact there is always ‘cash on the side line’. No money ever really flows into or out of shares (apart from primary and secondary issuance). Existing shares are simultaneously bought and sold. The stock of shares and deposits actually never changes.

Viewed through this prism, the price of risk assets merely reflects a consensus indifference point between owning risk and cash. During ‘risk off’ moments, the indifference point falls relative to cash and other safe assets. ‘Risk on’ results in a higher equilibrium point. So increasing levels of deposits and cash from the credit cycle does nothing to sustain higher share prices.

Back to Japan and supply side deflation

Outside the share market, the deposit boom created a cancer, which undermines shareholder wealth. Businesses once protected by high capital barriers to entry are now vulnerable. Entrepreneurs with greater access to risk capital are prepared to knock down the walls of established businesses to create new, better and cheaper products in the same space.

Growing tired of low single digit returns on fixed income, entrepreneurs gradually begin to accept lower returns on equity for new ventures. Existing businesses trying to maintain +10% ROE and a share price of 1.5x book value begin to compete with new businesses willing to accept 7-8% ROE with capital at book value. Price deflation - and earnings downgrades - eventually follow.

Meanwhile, low official cash rates from central bankers alter business behaviour. All-in debt funding at 3% eventually allows new and marginal projects to proceed, adding to the supply capacity of the overall economy.

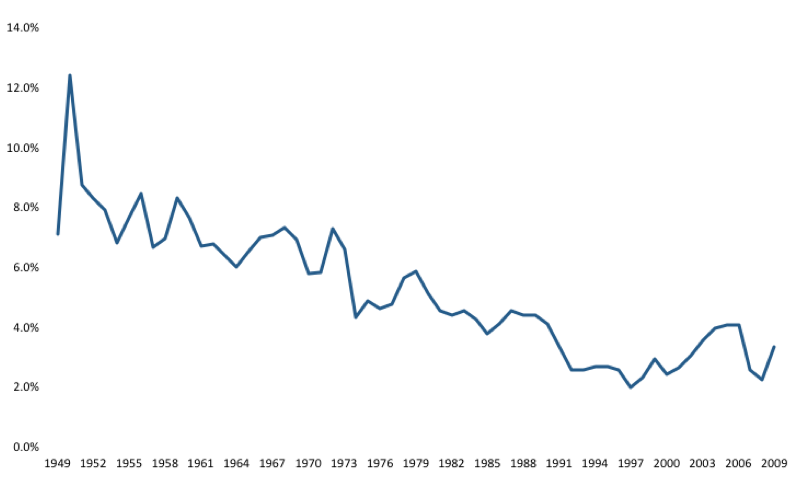

By accepting lower marginal returns on capital, and with new (well funded) entrants challenging existing business models, return on capital eventually declines. The following chart shows the Japanese experience.

Private Japanese return on capital employed

What has all of this to do with Australian superannuation?

The Australian superannuation system is legislated to grow. Indeed there is bi-partisan support for this policy – the only difference between the major parties is how quickly it should do so.

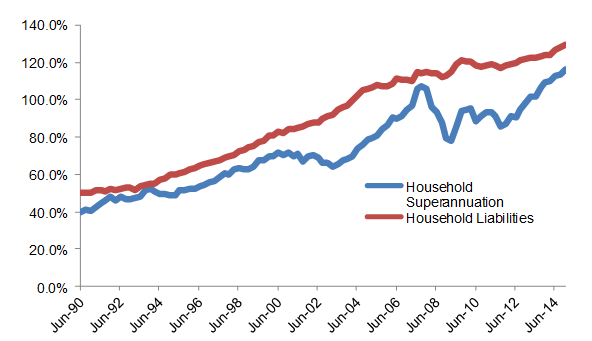

The latest statistics indicate superannuation is now $1.87 trillion to December 2014, representing 116% of GDP.

The scale of Australia’s superannuation system mirrors the scale of Australia household debt currently 129.9% of GDP. The loan created the deposit, and the deposit is searching for a return.

Australian Household Balance Sheets (% GDP)

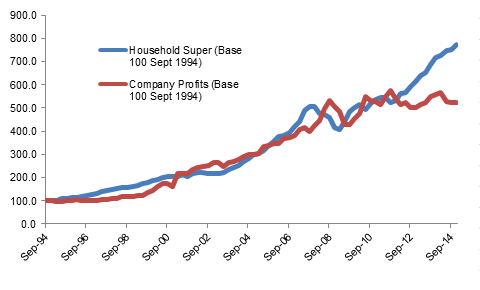

The problem is that the growth in superannuation is now significantly outpacing corporate profits. This means return on capital will fall. The only political debate remaining is how quickly we can dilute returns.

This is not good news for owners of capital. To avoid the dilutive effect of local superannuation policy one must seek returns offshore.

Australian Company profits versus Superannuation balances

Investment Implications

Over the long term, business return on capital is eventually the total return to shareholders. Price earnings ratios may move, but over time if business earns 3% return on equity, so too will the underlying shares.

We are already seeing the effects of this dynamic. Capital availability has ensured a boom in iron ore production – which has placed downward pressure on the ore price, pushing return on capital lower. Share prices have followed.

Globally, the same dynamic has occurred in energy (especially oil and gas). Share prices have also followed.

There is a domestic push for banks to hold more equity to support their mortgage books – which in turn will reduce bank return on equity.

In short, capital availability is no longer a barrier to entry and will act to reduce returns over time. Certain shares prices will follow.

Quay’s investment philosophy

At Quay, we believe the best real estate strategy to protect wealth in this environment is to find investments with the following characteristics:

- assets valued at or below replacement cost – no amount of capital can compete with the lowest cost producer;

- assets with physical barriers to entry such as best in class urban retail malls;

- assets likely to benefit from significant long term secular demand (e.g. health and assisted living); and

- assets located where they do not already represent the highest and best use (e.g. London storage and student accommodation, West Coast US office).

We believe investments in assets with these characteristics will help insulate investors from new capital formation aimed at eroding returns.

Conclusion

Investors who have reached a point in life where return on capital provides their income (or at least significantly supplements it), will already be aware that low interest rates erode their cash/term deposit returns.

But low interest rates and excessive capital will erode return on company-invested capital, which over time will affect equity returns. The process simply takes longer to play out.

The next time you read the financial section of the paper and it proudly states Australia now has $2 trillion in superannuation balances, ask yourself: how can this country, growing at 2-3% per annum, generate the output required to meet your return expectations?

We think it is prudent to think global.

Disclaimer

The content contained in this article represents the opinions of the authors. The authors may hold either long or short positions in securities of various companies discussed in the article. The commentary in this article in no way constitutes a solicitation of business or investment advice. It is intended solely as an avenue for the authors to express their personal views on investing and for the entertainment of the reader. In particular this newsletter is not directed for investment purposes at US persons.