Recent bond market mayhem

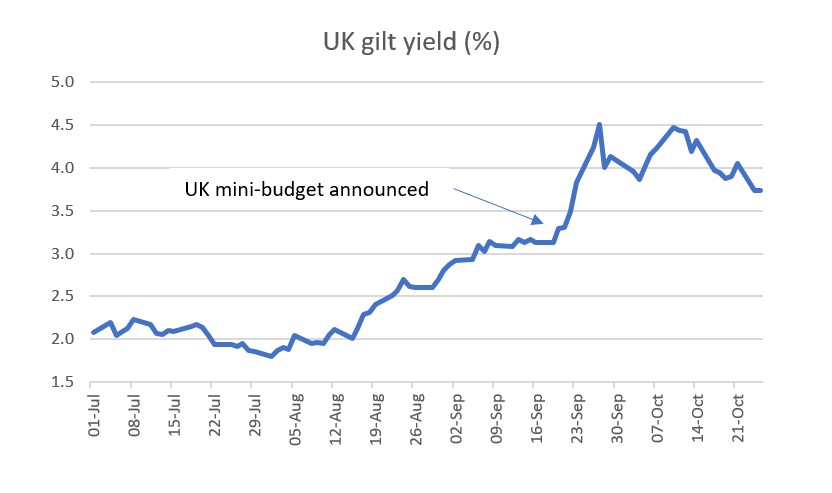

Last month, we witnessed an extraordinary turn of events in the UK. Then-sworn in Prime Minister Liz Truss and Chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng announced several fiscal initiatives (including support for soaring energy prices and tax cuts), which seemed to run counter to the rising inflation issue faced by the country.

The result was a sharp sell-off of UK gilts (long duration bonds), resulting in central bank intervention (buying) to provide liquidity and restore an orderly market. The UK government partially reversed the policy, both leaders fell on their swords, and yields began to fall back to levels prior to the policy initiative.

Source: Bloomberg, Quay Global Investors

Globally, however, bond yields continue to sell off around the world. There is now emerging commentary that bond investors are ‘back in the driving seat’[2]; essentially suggesting that if bond investors don’t approve of government fiscal (or monetary) policy, they will be punished by higher interest rates and broad economic pain, potentially leading to a sovereign debt crisis.

How sovereign bonds are priced

Government bonds are high quality monetary assets represented as a government liability of various durations that pay regular coupons. ‘Cash’ is no different to a bond in that it is also a government liability, but it differs only in that it is zero duration with no regular coupon.

Since a sovereign currency issuer[3] can never inadvertently ‘go broke’, the two assets (bonds and cash) are readily interchangeable.

Since cash and bonds are both essentially the same instrument outside of term and coupon, they are naturally priced relative to each other. Since cash is zero duration, it’s always priced at ‘par’, therefore it’s the bond value that changes relative to the face value of cash.

Over time, the duration of cash and a bond is the same. For example, the duration of cash held for three years is the same duration as a three-year bond. Therefore, the relative price between cash and bonds is based on the relative interest rate for each.

We know the yield of a three-year bond today. What we don’t know is the yield on cash over the three-year time horizon. That’s where central banks come in.

Since the risk of holding cash and a three-year bond for three years is the same, the return should be too. Therefore, the yield of the bond simply reflects investor expectation of the compounded return on cash over three years.

As central banks change their policy views to meet a certain economic situation, the expectation for cash returns change, and bond yields follow. For example, during the early months of COVID, bonds yields fell in anticipation of very low cash interest rates for a very long time. Indeed during 2021, central banks often stated interest rates would stay low for long periods of time, which meant bond yields stayed low too (trade-off between bonds and cash).

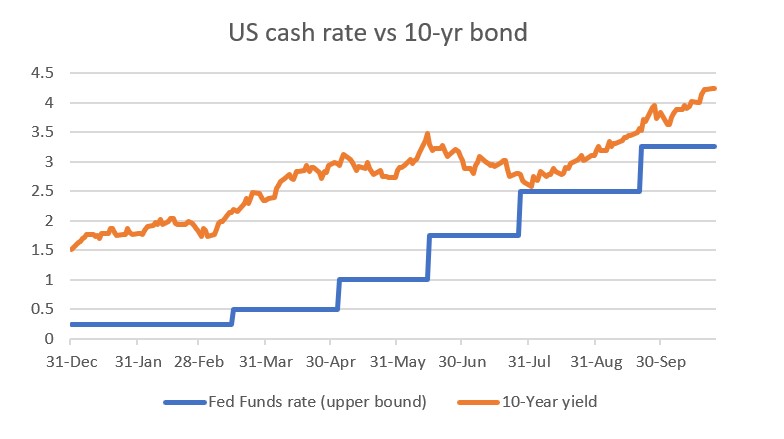

Since early 2022, central banks pivoted to tackle rising inflation. Well before the rising of the cash rates, bonds yields began to rise as market participants anticipated higher interest rates in the future. Eventually the cash rate ‘catches up’ with the bond yield as investors anticipate the end of the interest rate cycle.

Source: Bloomberg, Quay Global Investors

Back to the UK

The policy announcement by the UK government in August, which effectively increased fiscal spending to combat a slowing economy and an energy crisis, was followed by a sharp selloff in UK gilts. This wasn’t because bond vigilantes were sending a message, but because investors increased their expectations of higher future cash rates.

But of course, if bond vigilantes did exist, bond yields would have risen anyway. So, looking at the UK alone is probably not enough to make our case. We need to dig deeper.

Let’s talk about Japan

Unlike most of the western world, the Bank of Japan (BOJ) continues to:

- set official cash policy rate at -0.1%

- control the yield curve by setting the 10-year bond yield at 0.25%; and

- use various forms of quantitative easing.

Apart from the fact Japan has the lowest inflation rate in the world, there was also a recent policy change by the Japanese government. In October, the government announced a new ¥20 trillion economic package (US$133bn) aimed at households to cope with higher energy costs and boost the pandemic-hit tourism sector[4].

Unlike the UK experience, the ‘fiscal boost’ had no impact on the Japanese bond market, as 10-year bonds remain at 0.25%. The lesson is that any currency issuing central bank (such as the BOJ), if it so chooses, can stare down so-called bond vigilantes under any economic circumstances. Those that have ever doubted this were subject to the infamous widow maker trade[5].

Moreover, liquidity in Japanese bonds has all but dried up, with 5 successive trading days in October where there were no secondary market transactions[6]. Despite the illiquidity, the price (yield) remained unchanged, indicating speculators (vigilantes) have all but given up trying to bet against the central bank.

The fact that bond yields are higher in other economies simply reflects an unwillingness for central banks to set the price beyond the targeted cash rate. Of course, this is nothing more than a policy decision and could change at any time (as per the UK).

Currency vigilantes?

So while it’s true bond vigilantes do not exist, what about currency vigilantes? What about the stark sell-off of the UK pound or the Japanese yen?

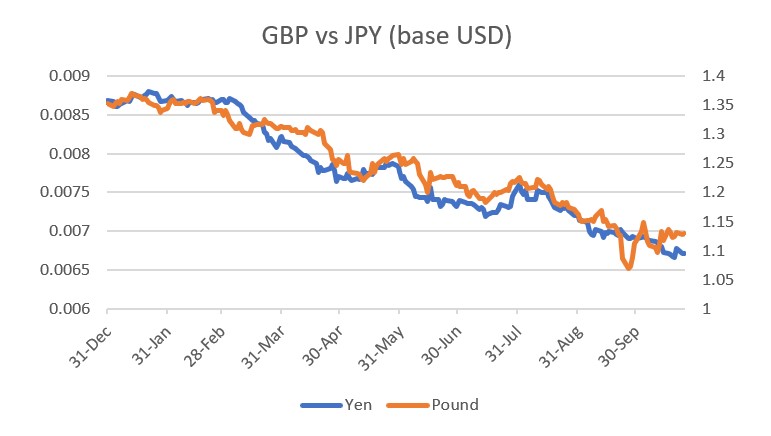

By definition, currency sovereigns have a free and fair floating exchange rate. Central banks are unable to permanently support the exchange rate. To that extent, market participants have a greater ability to impact the value of the currency. But is the yen being punished more than other currencies for its recent fiscal expansion or low monetary setting? Based on the data so far, not yet.

The following chart dispels the notion that countries must raise interest rates to ‘defend’ their currencies – the sterling and yen have moved in lock step (relative to the USD), despite significantly different monetary policy settings. Of course, this does not mean central banks will not buy the myth and raise interest rates anyway, but there is no guarantee such action will defend the currency.

Source: Bloomberg, Quay Global Real Estate

What the bond market is telling us

In short, a rising bond yield tells us market participants are predicting higher central bank interest rates due to central bank rhetoric and recent robust (US) economic data. The moment that changes (weak data or a change in messaging), bond yields will fall in line with lower official cash rate forecasts.

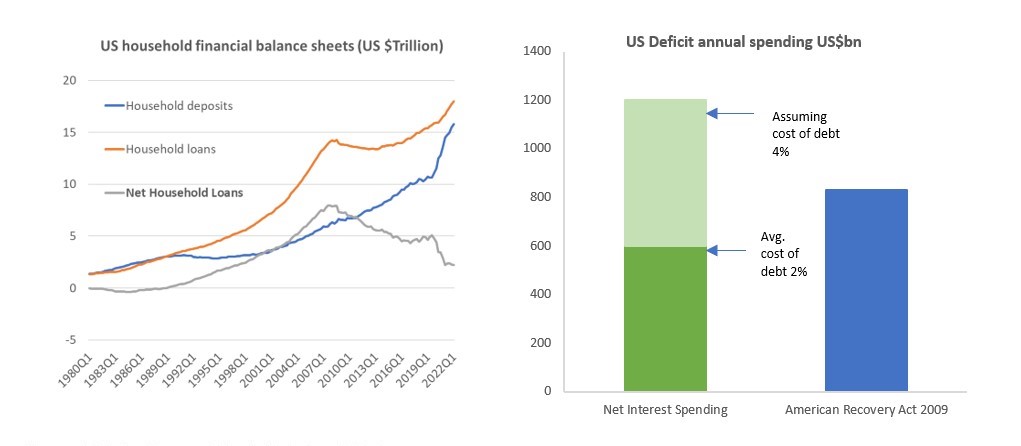

Our main concern as it relates to the US bond yield is not the existence of vigilantes, but the view that the US central bank has the entire interest rate policy setting backwards. That is, given the sheer size of US government debt, and the robust nature of household balance sheets, higher interest rates are acting as a type of stimulus in the current environment. As the second chart below (on the right) highlights, as interest rates rise to, say, 4%, government spending via interest payments will increase to $1.2 trillion per annum – significantly greater than the 2009 GFC stimulus package of ~$800 billion.

Source: US Federal Reserve, St Louis Fred, Quay Global Investors

Conclusion

Bond markets have been volatile all year. We expect this to continue, part of which can be explained by changing expectations of future interest rate policy, and part on technical issues (such as the recent UK gilt sell off). Bond vigilantes are not a factor.

At Quay, our focus is to identify excellent long-term real estate companies via a bottom up stock selection approach. That’s not to say we are not aware of the macro environment, but we save a lot of time NOT worrying about issues that don’t exist. As it relates to monetary sovereigns, we don’t spend any time worrying about bond vigilantes or a sovereign debt crisis.

[1] https://www.investopedia.com/bond-vigilante-6386194

[2] https://www.reuters.com/markets/europe/bond-vigilantes-mean-business-governments-better-beware-2022-10-17/

[3] https://www.quaygi.com/insights/articles/investment-perspectives-modern-monetary-theory-and-why-youre-about-hear-lot-more

[4] https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2022/10/21/business/economy-business/kishida-government-extra-budget/

[5] https://www.investopedia.com/terms/w/widow-maker.asp

[6] https://finance.yahoo.com/news/1-japan-10-jgbs-trade-061746599.html

The content contained in this article represents the opinions of the authors. The authors may hold either long or short positions in securities of various companies discussed in the article. This commentary in no way constitutes a solicitation of business or investment advice. It is intended solely as an avenue for the authors to express their personal views on investing and for the entertainment of the reader.